The geographical divide is basically the width of the Ohio River. On one side, you are in a distinctly Midwestern part of the country. On the other, you are in decidedly southern land. You can find a wealth of Dixie flags, the sewn song of the South, in eastern Indiana. And you can find plenty of (formerly) industrial areas and Democrats in the South. Stereotypes are stereotypes for a reason, but they are limited in scope.

The long, wet border between Kentucky on one side and Indiana and Ohio on the other separates what are supposed to be entirely different populations with entirely different beliefs, voting for entirely different people and rooting for entirely different teams and, in college football’s case, conferences.

Last year, I went on a road trip through the South, attending my first SEC football game and visiting seven SEC college towns and three honorary SEC cities (Memphis, Birmingham and Atlanta). This year, with that trip still relatively fresh in the memory, it was time to make a similar trip through the Big Ten to compare the regions and get a taste for Midwestern football culture.

I picked up a friend at the airport on Thursday and dropped him off on Monday. Below is the story of what happened (and where) in between.

![]()

THURSDAY

This trip almost didn't happen. My friend Walsh, last year's road trip partner, was supposed to go with me through Big Ten country as well, but as in many sequels, the cast changes, even at the last second. Walsh started a new job and couldn't get the time off he thought for the trip. With fewer than two weeks until the departure date, I threw a Hail Mary in search of a friend who I could stand to be in a car with for more than four days (and who could similarly stand to be in a car with me): Eric.

My best friend from high school, Eric is the older brother of Trent Ratterree, star of Chapters 2 and 11 of my book, Study Hall. Trent played for Bob Stoops, Kevin Wilson and company at Oklahoma, and when we were young, Eric pretty regularly got grounded for picking on Trent too much. My overnight stays were often cut short for this very reason. Eric likes to tell you about a series of pictures from a family vacation to Oregon. Picture 1: Eric looking at the camera with Trent throwing what look like rocks or pebbles at Eric in the background. Picture 2: Eric chasing Trent. Picture 3: Trent crying.

Eric and I see each other a couple of times a year. We say we've been best friends since we were two. We had our adversarial moments growing up; in line from recess, he cut between me and a girl I liked, and I took a swing at him. I still feel guilty that he got swats for it, and I did not. But safe to say, that claim is mostly true. We hung out all the time in junior high, and we hung out when we were both single in high school. Priorities, you know. I don't have an enormous extended family, so I got to choose mine, to an extent; and the Ratterrees were always family. I even agreed to wear an Oklahoma shirt (with a Mizzou shirt on underneath) to a Missouri-Oklahoma game in Norman in 2007 so I could sit in the family section at Owen Field. Now that's love.

Eric hadn't seen much of the Midwest before. He followed OU around for years to watch his brother play, but other than Cincinnati in 2010, the Sooners didn't make many trips to this area. His family has gone west for quite a few vacations, but he had never been to Chicago. Meanwhile, what felt like half of my dorm floor was from Chicago, and I got to know the place pretty well. Between the two of us, we’ve covered just about the whole country; but we haven’t necessarily overlapped that much. And we’d somehow never really been on a road trip together. We have now.

Iowa City

The town of Hills, Iowa, a few miles outside of Iowa City, is a total lie.

Southern Iowa pummels you with corn and emptiness. It leaves you no choice but to talk about it.

Even when you think you're prepared for it, southern Iowa seeps into your consciousness before you even realize it, through the backdoor if necessary. I began to recognize this on the tail end of a five-minute debate about the corn fields we were passing, which ones might be for ethanol, and which ones might be for food. "It seems like some of these are almost intentionally more dried out than others. I mean, they look dead, but these across the street are pretty green. That couldn't be an accident, could it? So the drier ones are for ethanol maybe?" Southern Iowa pummels you with corn and emptiness. It leaves you no choice but to talk about it, even if you are incredibly uneducated about the topic.

That said, Iowa City is college-town nice. The stands inside Nile Kinnick Stadium are quite vertical and, I assume, loud. The concourse decor feels straight out of 1953. You feel like you are walking through a black-and-white television. It is so very, very Big Ten.

Kinnick Stadium is where No. 5 Iowa whipped No. 3 Ohio State in 1960. It is where No. 1 Iowa beat No. 2 Michigan in 1985. It is where the Hawkeyes beat three ranked teams in 2003 (including Michigan again) to announce its completed return to big-time football after a surprising run in 2002. And it is where painfully loyal fans still show up in droves to watch a mediocre (at best) football team limping through another attempted recovery. Iowa's average home attendance in 2012 was 70,473. It is Hawkeye fans' own fault, really, that head coach Kirk Ferentz is still there — as long as the turnstiles are turning, Iowa doesn't have an immediate reason to make a move. But they keep showing up because what else are you going to do? Football’s fun, and Iowa City is a pretty fun place to visit considering the surrounding areas.

Almost every college town has a college downtown, be it one square block or 100. Iowa City's, across the Iowa River from the football stadium and a good portion of campus, is bigger than many. You've got all of the noodle places you could ask for, and you've got bars, trendy shops, Iowa apparel stores and trinket boutiques. You've got a former state capital, which is surrounded by lawns in a layout reminiscent of Springfield, Ill. You've also got Short's Burger & Shine, which came highly recommended.

Locally sourced food is a pretty big deal for some these days, and it’s fun to see Short’s brag about how its “beef has not traveled far. Only 26.5 miles to be exact.” Ed Smith Farms provides the meat, and Short’s provides the toppings. Since it's 3 p.m., and we've still got three hours of driving to do, we skip the shine, but Eric enjoys a Baxter burger (blackened, bacon, provolone, chipotle mayo) while I throw down a Gravity (caramelized onions, bacon, green chili, jalapeño cream cheese), fries, and a couple of pints of local brown ale. The fries are salty, and the burgers are big enough, but not so big they fall apart. Every college town has a noteworthy burger place, but this one’s better than most.

North of Iowa City, the state turns scenic. Part of that is because we choose to avoid the interstate, and part is because we go though Dubuque, one of those surprisingly gorgeous towns on the Mississippi, like Stillwater, Minn., or (to a lesser extent) Quincy, Ill.

Because Eric and I haven't had much time to chat in recent months, the conversation is still going strong. Family, kids, a little bit of politics, stories from previous road trips of his or mine, lots of sports. Of course, lots of sports. And even if the conversation had begun to lag, then figuring out what the enormous M outside Platteville, Wis., stood for — and with no phone signal to look it up, no less — would have gotten it going again.

We are talking enough that we almost run out of gas in central Wisconsin, both because we weren't watching the fuel gauge and because the car lied to us: 54 miles of gas range turned to 45, to 40, to "Yeah, dude, you've got like 20 seconds to find a gas station" over the course of about five minutes. In what I thought was a 15-gallon tank, I put in 15.446 gallons of gas.

As the sun sets on Thursday evening, corn turns to dairy, and Madison approaches.

![]()

Friday

Madison

"Bret Bielema was a dumbass."

When I ask Eric what he thinks of Madison as we prepare to leave on Friday morning, that's all he can think to say. I tried as hard as I could not to build expectations too high, but I shouldn’t have worried. Over the previous 12 hours, we've eaten brats and curds, we've had beer in Memorial Union, walked down the most college town strip of all college town strips in the country. We've walked by the capital, thrown down a ridiculously good cup of coffee, and spent a couple hundred dollars at the university bookstore. And thanks to some fortuitous timing, we've walked in and around Camp Randall Stadium.

Both the city and university it holds are the prototypes for college towns and higher education experiences.

Madison is college. Both the city and university it holds are the prototypes for college towns and higher education experiences. The city has all of the culture, shopping, beer and food you could ask for; the university has Bucky the Badger, Camp Randall, academics and Jump Around.

I had my first order of cheese curds in Madison (at State Street Brats, I believe), and I bought my first Charles Mingus album (in the B-Side Records jazz room) in Madison. That pretty much explains it all. You can drink a Capital Amber by the lake(s), and you can find a shop for every nationality within a block or two of State Street. My wife could care less about Mingus, but this is just about the only place in the world where I could travel that would make her jealous. She misses it, too. She would move here in a heartbeat if not for winter. And by winter, I mean the period between November and May. In the Midwest, you take full advantage of the times that weather allows you to go outside and enjoy yourself. The rest of the year, you hole up and wait. Or play hockey.

Honestly, this entire trip was probably just an excuse to go back to Madison. Find your own excuse, but definitely get there at some point. Have some Capital and some New Glarus. Eat some sausage. Sit next to a lake. Buy a Bucky shirt. Walk and walk and walk. Then find a reason to go back.

![]()

It’s about midnight as we walk back down State Street toward our hotel, and things are picking up a bit. The NFL’s season opener is over, the wait for a brat looks a bit longer, and students are milling about, either departing from where they were hanging out or just getting there in the first place.

Eventually, we have to leave, a little groggy but not quite hung over. We get out of town about two hours later than we intended on Friday morning, but there was just no choice. This city refuses to let go of you without a fight. After a stop at Camp Randall, we escape. It’s amazing, by the way, how Wisconsin fans seem to have scored the trademark on fun. As we will learn, Big Ten student sections know what they’re doing and know how to milk the game day experience for all it’s worth, even with those god-awful 11 a.m. kickoffs. But between the start-of-fourth-quarter shenanigans and one rousing YouTube rendition of “Build Me Up, Buttercup,” Wisconsin seems to have cornered the market. I’m all right with this.

***

![]()

Eventually, we head south and east into the Land of Lincoln and endless construction. We drive through a construction zone for a good 80 straight minutes on the infinite outskirts of Chicago, but we eventually get there to pick up Sosa, a college friend of mine, downtown. Letting Eric drive at this point was probably a mistake, as he spends much of his time looking up at the buildings he's seen in movies (that one got destroyed in Transformers! There's where that one scene in Dark Knight was filmed!) instead of the traffic lights. And from downtown, we inch back north toward Hot Doug’s.

Since Doug Sohn’s “sausage superstore” was featured on Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations, food nerds already know about it. But it’s rare to reach nationwide cult status and still be adored by locals. Usually there’s resentment after a while. But every Chicagoan who heard where I was going first expressed jealousy, then recommended the duck fat fries. When I posted a picture of the foie gras dog I was about to destroy, I got multiple “That’s my favorite thing in the world” responses.

Balancing cult and mainstream love is difficult, but it’s understandable when you combine both Doug’s personality — he chats you up, takes your order and treats you with kindness — and the disturbingly fantastic product. Like Madison, I feared expectations would be impossible to reach, but I shouldn’t have worried. The foie gras duck sausage with truffle aioli, foie gras mousse and fleur de sel (only $10!) was somehow not too rich. The Shrimp ‘n’ Grits dog (smoked shrimp and pork sausage, creole mustard, grits, and goat cheese) was salty enough to cut through the richness. Eric’s Sonoran Dog (jalapeno and cheddar dog with jalapeno mayo, jalapeno bacon, pinto beans, tomatoes, and onions) was powerful, but wasn’t an endurance test. It didn’t even give him the heartburn he feared. And yes, the duck fat fries were divine. I think part of the draw is mental (I’m eating fries cooked in duck fat, and everybody loves them!), but no complaints.

Evanston

“Sports are fun.”

It's 85 and humid, but the breeze on the rocks off of Lake Michigan is still pretty chilly. You realize this, and then you realize just how damn cold this place must get in January. Kevin Leonard, archivist and Assistant Director of Special Collections at Northwestern University, is trying his best to explain to us why Northwestern kept football in the 1930s and the University of Chicago did not without simply saying “Pssh, ask them.” Chicago's Maroons were an early football powerhouse under Amos Alonzo Stagg (after whom seemingly half of the country's football fields, leagues and trophies are named); he coached there for 41 years, also spending some time as the baseball and basketball coach. After he was pushed out there, he ended up at Pacific for another decade and a half, served as an assistant in a couple of places, and retired at the age of 96.

Chicago halfback Jay Berwanger won the first Heisman Trophy in 1935, and the school was associated with 11 College Football Hall of Fame inductees. But following an atrocious 1936-39 stretch that saw the once-proud program win just six games, Chicago decided it could not maintain its academic standards while supporting a successful program and dropped the sport. In their final season, the Maroons beat Wabash and Oberlin, narrowly lost to Beloit, and dropped their other five games (to Harvard, Michigan, Virginia, Ohio State and Illinois) by a combined score of 300-0.

Forty years ago, the U of C picked the sport back up again, but only at the Division III level. So hey, when Big Ten commissioner Jim Delaney makes good on his threat to drop the Big Ten schools to DIII if players start getting paid, Chicago can rejoin the conference again and show its new/old conference mates around. It’s nice to have a tour guide.

As Chicago was gasping for air in the burgeoning world of big-time athletics, Northwestern was just beginning to thrive.

As Chicago was gasping for air in the burgeoning world of big-time athletics, Northwestern was just beginning to thrive. The Wildcats had enjoyed solid seasons here and there, but spent most of their early decades vastly overshadowed by the nearby Maroons.

In 1935, Pappy came to town. Lynn "Pappy" Waldorf took over the Northwestern program after six years and four conference titles between Oklahoma A&M and Kansas State. The Wildcats reached No. 1 in the polls in 1936 after taking down previous No. 1 Minnesota, and they even outfoxed Michigan in Ann Arbor before falling in the season finale at Notre Dame. Still, they managed to finish in the AP top 20 under Pappy five times between 1936-43, peaking at seventh. They signed the 1930s version of a five-star recruit in quarterback Billy DeCorrevont in 1938. Coaches discovered basketball star Otto Graham playing intramural football on a field across from campus, and he finished third in the 1943 Heisman voting. Northwestern football mattered under Pappy.

Waldorf left for California after the war, and as Leonard subtly puts it, there were some bumps. Northwestern labored under Robert Voigts and, for one year, Lou Saban. Ara Parseghian took over, and Northwestern reached No. 1 for two weeks in 1962, beat Notre Dame four years in a row … and lost Parseghian to Notre Dame. Fortunes were decent, then bad, then horrific. Northwestern won more than three games in a season just once between 1973 and 1994.

Even now, after Gary Barnett took the Purple to Pasadena in 1995, after Randy Walker helped to redefine college football offenses a decade ago, and after Pat Fitzgerald (who took over when Walker tragically passed away in the summer of 2006) ripped off a string of five consecutive bowl seasons and established residence in the top 20 of the polls, it doesn't take long to sense how limited Northwestern's capabilities are. The football stadium, the athletic campus as a whole, is landlocked, and the surrounding area of Evanston is more city than college town. If ever there is a need to expand the football stadium, or anything else within the athletic campus, good luck with that. There's nowhere to expand. (There's really nowhere to tailgate before a game, either, which is a shame.) The last time the school needed more land, it ended up filling in part of Lake Michigan. You can probably only get away with doing that so many times.

School doesn't even start until Sept. 30. Northwestern's first three home games this season take place before students even have a reason to show up to campus. And the Big Ten Network revenue that has done (and is doing) so much for so many conference members goes through the school first, then reaches the athletic department.

To catch up with the Big Ten's Joneses in the facilities arms race, the school will have to build closer to Lake Michigan than the current athletic campus, but even though this will really only catch the department up to most of the rest of the conference, and not really put NU ahead of many, Pat Fitzgerald calls it a game changer. If you're used to figuring out how to win games while at an extreme disadvantage, you don't exactly need many tools to feel excited about your chances.

In the end, it's worth the neverending, uphill fight.

In the end, it's worth the neverending, uphill fight. This is a small, elite school, with a small alumni base — the city of Chicago, which sits on the skyline to the South, houses more alums of every other Big Ten school than it houses Northwestern grads (which doesn't stop either NU from calling itself "Chicago's Big Ten school" or fans of other school from mocking that slogan) — and minimal room for physical growth still plugs away. Why? Because sports are fun.

As with every other school with an athletics program, sports give Northwestern alums and old friends a reason to meet up with each other each fall, to relive That One Time and That Big Win: 54-51 over Michigan in 2000, 24-0 over Oklahoma in 1997, 17-15 over Notre Dame in 1995, 31-6 over Northern Illinois in 1982 (the one that broke the losing streak), 17-8 over Ohio State in 1963 (Parseghian's final game), 35-6 over Notre Dame in 1962, 45-13 and 19-3 over Oklahoma in 1959-60.

In the absence of Olympic-caliber facilities and the ridiculously large fan base enjoyed by so many conference mates, the Wildcats have gone about competing by means of hunger and energy. Hire fiery, young individuals and go to work. Head football coach Pat Fitzgerald, a linebacker on the 1995 Rose Bowl team, is still only 38 and just began his eighth season in charge. His intensity is obvious just from watching him on the sidelines; as you walk into the athletic facilities, you are welcomed by a glare from a stuck-on version of Coach Fitzgerald on the left side of double-doors. You reflexively use the right door to enter.

But it’s not just Fitzgerald. New basketball coach Chris Collins was a senior at Duke when Fitzgerald and company were winning the Big Ten 18 years ago and is still shy of 40. Even the Sports Information Director, Paul Kennedy, is a young guy.

Northwestern has continued playing football for the same reasons everybody else plays football: Because the school likes it. It just doesn't like it enough to change too much. And after a bumpy few decades, the decision to keep right on playing football seems to have been a good one.

Other things we learned during our walking tour with Kevin Leonard:

* In 1933, a proposal to merge Northwestern and the University of Chicago actually got pretty far before faltering. That’s a shame. The Norcago Marooncats would have dominated.

* There's a webcam looking down from University Hall on to The Rock, which is the primary campus landmark.

* Leonard and his team have come across an outright treasure trove of a football film vault and are trying as hard as they can to get as much of it digitized and online as possible. I wish every school in the country was doing this. College football is an important part of academic life for so many, but the sport's history is fractured, regionalized, and, in no way unified. That's a shame.

We inch back toward downtown down Lakeshore as Eric and Sosa talk about previous beach-going experiences (because the Lake looks as pretty as I've ever seen it right now). I'm driving, so Eric can look at whatever buildings he chooses. And damned if the GPS doesn't get all sorts of confused when trying to figure out whether you're on Lower Wacker or Upper Wacker.

After dropping Sosa off, we cruise on toward South Bend, our stop for the night. It isn't Big Ten country, but a) it might as well be, and b) it's a couple of hours closer to East Lansing so we don't have to get up as early in the morning. We get to our hotel, trudge off to Fiddler's Hearth for a nice boxty dinner at 11:30 p.m., and hit the sack.

![]()

Saturday

South Bend

“I just hate them so much.”

One of the perks of writing for SB Nation is that everybody knows your allegiances from the start. You don't have to hide them, but you are not a prisoner of them. I find it easier to be impartial when everybody knows my deep-seated biases up front (even though I feel I’m successful in not letting them leak into my work). That I run SBN's Missouri blog is right there in my bio, but if a conference (or border) rival is good at something, I'm not going to avoid talking about it just because I'm a Mizzou fan. Call it fan maturity, I guess. I can accept and acknowledge reality, and I can enjoy other campuses and teams, without affecting my original loyalty. Eric can, too …

… as long as Notre Dame's not involved. You see, Notre Dame has had a little bit of success against Oklahoma through the years. And by "a little bit," I mean the Irish have won nine of 10 all-time meetings versus the Sooners. I'm sure that OU's 40-0 victory in 1956 was very satisfying and all, but a) that's it, and b) that was 57 years ago. As with Alabama fans, getting owned in any head-to-head series nags at a Sooner fan. It's hard to accept. (It's easier to accept for a Mizzou fan.)

the school elicits strong feelings out of everyone, really, one way or the other

![]()

That the Irish took down the Sooners in Norman last year on the way to a BCS title game bid just exacerbates all of the bad feelings — the school elicits strong feelings out of everyone, really, one way or the other —– and it makes Eric very, very bitter toward Notre Dame. I think he dislikes them more than he dislikes Texas. It amuses me.

The first thing you notice about South Bend is that … well, it doesn't put its best foot forward near the highway. It looks like a lower-class Terre Haute when the interstate is still in view. Granted, the Dunkin' Donuts across from our hotel was a welcome sight, but we were not exactly blown away by the town when first driving around. But as you work your way south toward both campuses and the downtown area, you are at least a little bit charmed by both the greenery and the history of the buildings surrounding you.

Notre Dame's stadium is the first one we can't get into on this trip — in Iowa City an usher let us in to take pictures, in Madison the stadium was just open, and in Evanston we got a heck of a tour — but that fits. We don't let just anyone through these doors, son.

We meet briefly with a friend of mine, Football Outsiders' Brian Fremeau. I've been working with Brian at FO for five years now, but this is our first face-to-face meeting. We take a picture with Touchdown Jesus blessing us, and we walk around the stadium and check out all of the statues; I love the Parseghian one, and I love that there was consternation about giving Devine one, as if winning only one national title and being mean to Rudy in Rudy (though not necessarily in real life) made him damaged goods.

We also try to figure out why someone left two hot dogs at the feet of Knute Rockne. Eric and I had decided that this was some sort of ritual we hadn't ever heard about (and from this point forward, it should be), but Brian says there was a student gathering with hot dogs at the stadium the night before. I like our theory better. "Somebody better give Knute some more hot dogs" becomes an actual joke that night during the game. And you can’t prove that one more dog wouldn’t have gotten the Irish over the top.

East Lansing

“There is a ton of stuff I would do in East Lansing as an alum … cruise for 4H babes … throw stuff off the bridge.”

I used to go road-tripping to concerts with a Michigan State friend. Joey and I liked most of the same bands, though we never liked the same songs, and we sometimes had different motivations for going to shows. Or, to put it another way, we had our own ways of having fun at them. I've since learned over time that he's pretty damn conservative, which bucks quite a few stereotypes as well. Regardless, as Eric drives us through construction zones in southern Michigan toward the state's capital and Michigan State, I exchange texts with Joey to get a read on what we should absolutely do while in East Lansing. His first response was to quote Tommy Boy. That tells you quite a bit.

(Actually, no, his first response was to recommend the MSU Dairy Store. And after trying it on the way out of town, I recommend it, too.)

State cannot quite shake the feeling of being a college within a city, not the hub of a College Town™

Michigan State's campus is quite pretty and, like most Big Ten schools, expansive. Like Wisconsin's (and unlike Iowa's), the field is reasonably close to ground level, which means the stadium juts high out of the concrete south of campus. You can't miss it. The town itself is connected to Lansing, obviously; Lansing isn't exactly enormous, but State cannot quite shake the feeling of being a college within a city, not the hub of a College Town™. You don't exactly see waves of Spartan green everywhere you look until you get awfully close to campus, but once you're there, you certainly know where you are.

I've always had sympathy for the second-tier football programs in a major conference, and for obvious reasons. There is, or there should be, a brotherhood of sorts among fans of programs that can make a run at a conference title or, on super-rare occasion, the national title once, but struggle mightily to maintain their momentum while bigger, richer, more historically strong programs continue to hack away at them (and potentially steal your coach as he's doing too well against them). Joey and I quickly recognized the similarities between our programs long ago and have rooted for each other out of solidarity. So when Eric suggested when-in-Roming it and buying State shirts before we headed toward the stadium for MSU-USF, it didn't strike me as an odd idea at all. We all have our different ways of role-playing, I guess.

![]()

We buy a couple of lower-level seats from a scalper (one who was hopefully going to Ann Arbor that night to join a much more high-stakes scenario) and move toward the stadium. It's a pretty customary experience, really: You've got your drunk 22-year-old trying to start his school's call-and-response cheer among a crowd of about eight people; in State's case, it's "GO GREEN." "GO WHITE." Or, in this guy's case, "GO GREEEEN. [go white] GOOOOOOOOO GREEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEN. [no response] COME ON. GOOOOOOOOOOOO GREEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEN."

You've got your clusters of dorm rats, your families of six, your small children getting overwhelmed by the fast walkers around them, your buskers, your food truck. You walk across a small bridge overlooking a creek, which is a nice touch, and then you get to an under-construction Spartan Stadium. The rarest part of the experience is the unexpected storm delay we encounter when we get inside. "A lightning strike within 15 miles" delays the game for about an hour, though while we never actually hear any thunder from under the stands, we are woefully unprepared for rain (hell, it hasn't rained in weeks where we each live), and this gives us an excuse to hide from some downpours and talk to some State fans.

When the game actually starts, it is a caricature. It is what you'd imagine if you were jokingly talking about how awful this game would be. “The State defense will probably outscore the offense again.” “USF will probably complete, like, 30 percent of its passes and go nowhere with them.” “[Random Michigan State QB] will probably suffer an egregiously ridiculous turnover.” “There will be, like, 200 or fewer yards of offense in the first half.”

The less said about the actual game, the better, though I will note that State fans are very earnest, if scarred. There was no Bronx in their cheers following the rare good offensive play, even though they had to know a silly mistake was forthcoming. With each increasingly hilarious miscue, the meltdowns around us became louder. My favorite victim was a couple of rows ahead of us; he went through each stage of fan madness, from “WE CAN'T EVEN FIND A KICKER WHO CAN MAKE A CHIP SHOT” to “TWO THOUSAND DOLLARS. I WASTED TWO THOUSAND DOLLARS ON THESE SEATS. THIS TEAM OWES ME MONEY.” But when fortunes improved for the team (a 7-6 halftime lead turned into a 21-6 coast with, yes, two defensive touchdowns to one offensive touchdown), he was puffing his chest and looking around, trying to make semi-cocky “I knew we were going to be all right, and I bet you feel stupid for doubting them” eye contact with those around him. Fans are great.

To make sure we get to Ann Arbor with plenty of time to spare, we do duck out a little early, shaking hands with the fans around us and making our way to MSU Dairy. Before we leave, though, Eric gets his first taste of a Big Ten band and a Big Ten student section. The students refused to leave their seats pre-game, even under threat of lightning (while standing on metal bleachers), and the band was … well, bands in the Midwest are just more powerful, bigger. They're awesome. That, and Zeke the Wonder Dog chasing down Frisbees while USF kickers were attempting to practice during halftime made it worth the trip. And hey, even bad college football is still college football.

Ann Arbor

When you join in the quest, when you attempt to find a pair of scalped tickets to a huge event — like, say, the final scheduled Notre Dame-Michigan game in Ann Arbor — you basically become a character in a play. Well, Eric does, anyway. I fade into the background because I suck at negotiation. Call me the narrator.

Cast of Characters

Debra, a tipsy woman in her mid-40s, surrounded by a posse of nameless friends and scalping tickets for the first time. Over the course of five minutes, she will almost give them away for free, regroup, drift back out into the crowd, and sell them for $800 each.

Jackie Moon Guy, a man who is indeed dressed like Jackie Moon and carrying a football. He very much believes that having an identity and standing out from the crowd will make him recognizable and get him an edge of some sort. (That, or he just really likes mediocre Will Ferrell characters.) He carries himself like he knows what he's doing and scoffs at people asking for far too much money for only a decent ticket, but this knowledge doesn't get him into the stadium. It’s a seller’s market.

Adidas, a guy in a slick track suit who is following our path in reverse. We cross paths with him numerous times, and after he asks us if we’re selling the first time, we just exchange knowing nods with him with each pass.

Drunk Guy and Girlfriend, a college guy who clearly isn't used to night games* and is basically passed out standing up. His girlfriend, sober, dutifully drags him around the stadium a few times, attempting to keep him upright and somehow walk off what will be an incredible hangover the next morning. Her evening is clearly wrecked, but hopefully her loyalty will one day pay off.

* You've got to pace yourself throughout the day, man, and if I hadn't already known this was just the second night game ever at Michigan Stadium, I'd have been able to figure it out by the number of irreconcilable drunks we found staggering around before kickoff. Many of them had tickets, got into the game, and can't possibly remember a second of it.

The Guy Who Didn’t Make It, a Notre Dame fan leaning, passed out, in the same spot for a good, solid 90 minutes.

I Know What I’m Doing Guy, a student who swears he's got one ticket, but is looking for a second and keeps asking people what they think they would pay for the ticket he never shows them. He thinks he is playing third-dimensional chess. He is not. His girlfriend realizes this and is clearly tired of waiting around for a second ticket to magically show up, but he is defiant.

Omnipresent Cops who basically make sure nobody does anything dramatically stupid and laugh at the drunks as they shuffle by.

Uncredited, the hundreds and hundreds of people holding fingers in the air tentatively, knowing they're not going to find the price they're looking for, but not giving up quite yet.

The Michigan Stadium Press Box, which mocks me endlessly with both its magnitude and the fact that my request for credentials wasn't even mockingly denied (as it was at Michigan State) — it was ignored altogether. Because the "B" in SB Nation will always stand for "blog," I guess, and people will always hate the Internet. Your free seats and dinner trays are safe from the underwear-and-mom’s-basement dwellers, small-town radio and newspaper guys.

But I digress.

We knew our odds of finding a reasonably priced ticket were minimal, even if we lingered well into the second quarter. But we lingered regardless, doing laps around a stadium that is bigger than the Baghdad green zone. I'm pretty sure the distance from the entrance to the concessions there is the distance from the entrance to the FIELD at other places. It's big even before you get to the "holds 115K people" part, and even from the outside, you can tell exactly how loud it must be on the interior. The best players might mainly live in the South, but Big Ten fans bring it. So do the bands.

There are some pretty incredible football schools in this country.

You can frequently get decent deals if you are willing to wait and miss the beginning of the game. You can't here, though. Eric and I, Adidas, Jackie Moon, etc., are all still lingering, ticketless into the second quarter, at which point we go back toward downtown on Main Street. Eric did manage to have an incredibly unique scalping experience, though: He came to buy, and he sold instead. He watched from a block away as a drunk student knowingly laid a ticket on the ground and wandered off. He waited for her to return, and when she did not, he scooped it up. It was useless to him, but he sold it to another desperate student for $125 and even got a hug from a cute girl in the process. That's a mark-up of infinity percent.

What in the HELL is up with the 'cutoff mom jeans' look?

Still buzzing from the bonus cash, Eric decides he's going to ask a couple of girls a question that's been bugging us all day: What in the HELL is up with the "cutoff mom jeans" look? In both East Lansing and Ann Arbor, there were too many instances of girls wearing flat-assed, baggy jeans cut off mid-thigh, a look that isn't attractive even on attractive females. It is frustrating, and it renders moot a text I got earlier in the day from my Michigan State friend Joey: "It's mostly about the 'scenery' in East Lansing, which you will NOT get in Ann Arbor." Our girls are always prettier than your girls.

It is a ghastly, horrific idea to approach a girl and ask about her shorts, by the way, but who am I to stop Eric? I kind of want to know the answer, too. So as we're walking north on Main, he asks two of them at an intersection while we're waiting for the walk sign. They don't respond, either because they didn't hear (they were starting to walk away) or because who the hell is this creepy dude? We don’t get an answer, but he doesn’t get arrested, so that’s a net draw.

Downtown Ann Arbor is big and interesting enough to handle an extra 100,000 (or more) visitors without falling apart at the seams. The shirt shops were crowded, but navigable, and we were able to get into the Jolly Pumpkin at 5 p.m. or so without a wait. I had a potato pizza (fingerlings, bacon, mozzarella, Tallegio cheese, caramelized onions, rosemary) and Bam Biere, and Eric went with the Carnivores (pepperoni, fennel sausage, bacon, charred tomato sauce, mozzarella) and some whiskeys and Coke.

I somehow resisted buying both a "Bo Knows" shirt with Schembechler's face on it and a "Water covers 70 percent of the earth, Charles Woodson covers the rest" shirt for my daughter; of all the problems I had finding 3T shirts on this trip, that was in her size.

We make the longer-than-you-think hike north from the Big House to the downtown area, past the epic debris, ongoing tailgates, and deaf girls in mom shorts. We hang out a little while longer downtown before making our way to a friend's house. Amid a small crowd, we watch Devin Gardner win the game, almost lose the game, and win it again (with ample help from Jeremy Gallon). We eat breakfast at another friend's house in the morning, then it's time to tour the MAC. As one does.

![]()

Sunday

#Maction

"Why is the MAC even part of FBS?"

We're eating baked French toast and drinking Tonx coffee at my friend Ed's house. He runs The Power Rank, and we first met, perhaps to no one's surprise, at the Sloan Sports Analytics Conference a couple of years ago. We're talking about the planned route for the day — we are rolling through four MAC campuses on our way down to Bloomington — and Ed is asking rhetorical questions. Why is the MAC part of FBS? What's the goal? Would that conference (and, presumably, the Sun Belt and perhaps the new Conference USA) be better off in some other subdivision, fighting for a national title instead of a spot in the Little Caesar's Pizza Bowl? What do they stand to gain?

I don't really have any answers for this. Just last year, Northern Illinois got to play in the Orange Bowl, which is a hell of a payoff; it proved that, with the BCS structure in place anyway, the stakes can still be quite high for these programs. At the same time, after hanging close to Florida State, in part because of turnovers, the Huskies were eventually beaten by three touchdowns and were outdone from an athleticism standpoint to such a degree that people talked about them as if they'd been Hawaii-whipped. The greatest achievement a MAC school had ever pulled off resulted in a 21-point loss and derision.

Here's what we learned in our mini-MAC tour: These teams are making an investment.

Here's what we learned in our mini-MAC tour: These teams are making an investment. In what, I'm not really sure. But they're investing in something with no promise of a payoff. Hell, the slogan at EMU this year is evidently "The Law of the Price Tag," which … is not the most inspiring slogan I've ever seen. But the result of this investment is an environment that is a cross between big-time football and NAIA. You've got the Law of the Price Tag in Ypsilanti, Mich. and Sunday afternoon peewee football going on at Bowling Green, Ohio. You've got a damn large press box at Toledo and almost completely open access to the Ball State stadium while athletes are working out on the field.

Other notes from the MAC tour:

* Toledo actually has a campus feel. We were doubtful. When your university is housed in the middle of a pretty large city, the commuter feel is difficult to overcome, but with its old, white-stoned campus, its historic (read: old) football stadium, and the fraternities and actual campus life next door to the Glass Bowl, you've actually got a campus that cuts through Random Industrial Dreariness, Ohio. At least, it does in the portion of campus we saw. There was minimal lingering on Sunday.

* This was actually my second trip to Bowling Green. I came in 2002 to watch my Mizzou Tigers get destroyed by Urban Meyer, Josh Harris and BGSU. We should have known we were doomed in that game after we chatted up a local cop during a makeshift tailgate. He told us we'd fit in just fine around there as long as we didn't shit on the grass. We laughed. His response as he drove off: “DON'T SHIT ON THE GRASS.” This was evidently a real issue. Naturally, then, the smell of sulfur was dominant when we stopped by to watch the peewees at Doyt Perry Stadium.

* The MAC basically feels like Triple-A baseball. At Bowling Green in 2002, and at Ball State in 2003 (a much more pleasant trip with a more pleasant Missouri result, and holy moly, does Gary Pinkel like playing with fire and visiting MAC schools; Mizzou's headed to Toledo next year, too, and had a game scheduled at Miami until the SEC move caused some shuffling), we frequently saw school flags hanging below Big Ten flags. The Ohio State/BGSU combination was prevalent; “I wanted to go to Ohio State, but ended up at BGSU instead. Go team.” I got used to this phenomenon growing up in Weatherford, Okla., home of Southwestern Oklahoma State. It seemed every Southwestern fan was REALLY an OU or OSU fan. But SWOSU isn't a fellow FBS program. I respect ambition, and I will always defend the MAC for aiming high, for choosing the pursuit of temporary glory, of a single program-defining upset or bowl trip, over the pursuit of a lower-tier national title. But one does wonder if it's worth it sometimes.

* The only differences between rural Indiana and, say, rural Alabama are the temperature and the crops around you. The gas stations, the billboards, the choice of flags are exactly the same. If you’re from a small town, you consider all of this familiar and safe. If you’re from a city, you feel threatened in a way you probably didn’t understand before you felt it. I’m lucky in that I’ve been exposed to plenty of all worlds. I grew up in a town of 10,000. I went to college in a town of 100,000. I have spent weeks or months of my life in Chicago and Washington, D.C. There is value in each type of community, though I’ve got to say that the Dixie flags and the paranoid, defensive looks always give me pause and make me a bit sad. The world changes, and there’s no reason to fear it.

(Eastern Indiana did provide us with something we missed in southern Iowa, however: the Amish. I can talk about how the world changes, but their existence makes me happy.)

Bloomington

Kevin Wilson walks fast and talks fast. We got to Bloomington later than we hoped (driving through western Ohio and eastern Indiana takes as long as it feels), but that's all right because Wilson's Hoosiers don't practice until the evening anyway. He's here, but he's moving quickly. How are the parents? How's Trent? He's asking Eric questions and seems to be actually listening, but he's moving quickly, and he’s got work to do. Of course he does. Building a winner at Indiana is nothing if not work, and the Hoosiers' loss the previous night to Navy proved that there's still plenty to be done.

It's almost a rite of passage, really. When you are building a defense from scratch, you at some point must face Navy, with its Flexbone and its assignments and its cut blocks, to find out just how far you still have to go. Spirits are solid here, though. Everybody involved knew that this job would be difficult, if not nearly impossible.

So why did Wilson take the job to begin with? As his football operations assistant Billy Ray Johnson tells us, he felt the IU facilities gave them a “fighting chance.” He'll say those words a lot over the course of our tour. Fighting chance. That's all you can hope for if you are involved with the major IU sport that isn't called basketball. But from a logistics standpoint, the facilities are uniquely impressive. The coaches' offices are affixed to the north side of the stadium, looking straight down onto the field. The weight rooms are on the ground floor below. The academic facilities trace along the east side of the stadium under the stands; the training areas, locker rooms, and dining hall are under the west stands. It's all right there; even the athletic director’s office is separated from the football offices by a mere conference room. One could see how that might be a really good thing at times and a really bad thing at others.

![]()

Wilson has done as much as he can to set the table for success. Now he just has to grind and hope.

Under directive from Wilson, the interior of the complex has been made a little more visually interesting and less drab. Instead of cream-colored walls, you’ve got pictures of current and former stars.

Wilson's a smart guy. That's the adjective you hear infinite times from any Ratterree. He's an observer — according to Trent in my book, his favorite thing to say was “I just watch.” The answers would come to him from observation. The gears turn pretty quickly, and you certainly get the impression he’s a pretty intense guy, even at breakfast. “Did you do your homework? Got any tests today? Ready for practice after school? Gonna put your dishes in the dishwasher? Gonna pass me that bacon?”

IU's athletic history is not littered with gridiron success, and while the facilities have been upgraded, they still aren't what you would find at a Big Ten heavyweight. And as we will learn, Bloomington isn't the easiest place to get to or escape. It's an hour from Indianapolis on a state highway, but if you're coming from any other direction, you're going to be riding the two-lane roads for a while. It's nice when you get here, from both a logistics and aesthetics standpoint, but you still have to get here.

Wilson has done as much as he can to set the table for success. Now he just has to grind and hope.

When a football coach recommends a wings place, it's probably a pretty good idea to follow the advice. Upon Billy Ray's suggestion, we head down toward Buffa Louie's for dinner. I ask Eric how many wings he could stand to eat, and he just says “A lot.” So we sample. Hot. Hot Q. Honey Garlic. Garlic Parmesan. Be thankful you were not in the Impala for the final portion of the day’s drive.

Oh, and I recommend you avoid the upstairs region of the restaurant. That puts you pretty close to the bell that people can ring on their way out the door. It’s a neat feature, but when you don't know it's there, it'll stun the bejesus out of you the first time somebody pulls it. And when somebody pulls it, they pull it with force.

Barreling down foggy, swampy Indiana back roads toward Terre Haute, we finally begin to run out of steam. We eschew the omnipresent iPod playlist I created for the trip in favor of our eighth-grade basketball soundtrack. We rattle the Generic Rental Impala windows, bumping the Juice soundtrack and Doggystyle, and after Terre Haute we naturally encounter lane closures and more road construction as we approach Effingham, Ill., for the night. For all of the justifiable derision Kansas gets for being so flat, boring and Kansas, Illinois is worse. It is Chicago and nothing. And in Kansas, at least you get to drive 80 miles per hour. They know you want to get out of their state as badly as you do. Illinois just mocks you with construction and endless highway patrolmen.

![]()

Monday

every sports fan base in the country is exactly the same, with only geography and history making us different.

![]()

You believe in what you believe in. You’re raised how you’re raised. I like to say that 80 percent of every sports fan base in the country is exactly the same, with only geography and history making us different. That goes for populations, too.

The primary differences between the capital-M Midwest and capital-S South are the climate and the elephants in the room. In the South, you’ve potentially been raised to hate yourself for what your ancestors may have done or been associated with doing. You sometimes grow defensive or hostile toward outsiders because of this. In the Midwest, you are perhaps without some of the stigma, but if you want to be educated and elitist, or if you want to live in a small town and work on a farm, you have the same opportunities to do so. There are smart schools, football schools and both in both regions of the country. Weather keeps you indoors in the Midwestern winter, and it sucks the life out of you in the humid southern summer. And perhaps that creates differences in how we view and/or attend football games, but wherever you go, the love of football is not far from the surface.

Our drive through the Football Midwest exposed us to college towns and fried food and backroads. It was fun, but of course it was. That I got to do this with Eric was certainly an added bonus. We are proof that a single state border (Oklahoma and Missouri) can both create an entirely different living experience and mean absolute bupkus.

On Monday morning, as we’re preparing to leave Effingham, I catch myself watching part of HBO’s Marty Glickman documentary, Glickman. A former Jewish-American track star and beloved announcer for the New York Giants, New York Jets and just about every sport in existence, Glickman’s love of sport was boundless. The film ends with a Glickman quote about how the greatness of sport is in its power to bring people together. Never is that more true than when two old friends roll through unfamiliar country, popping in on college towns that host old friends every fall Saturday.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty Images

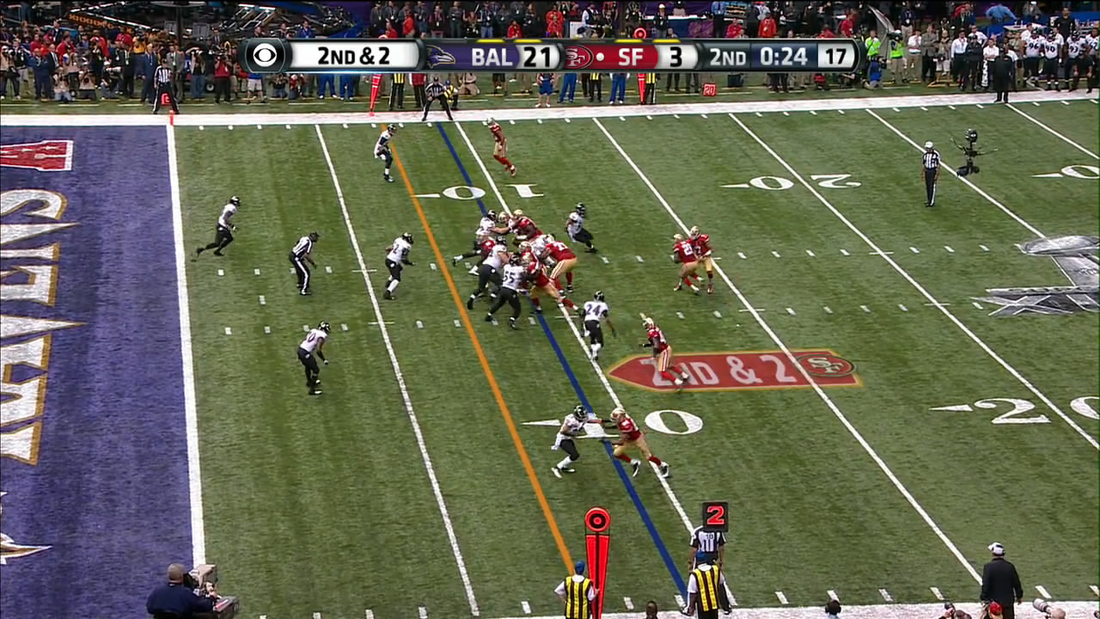

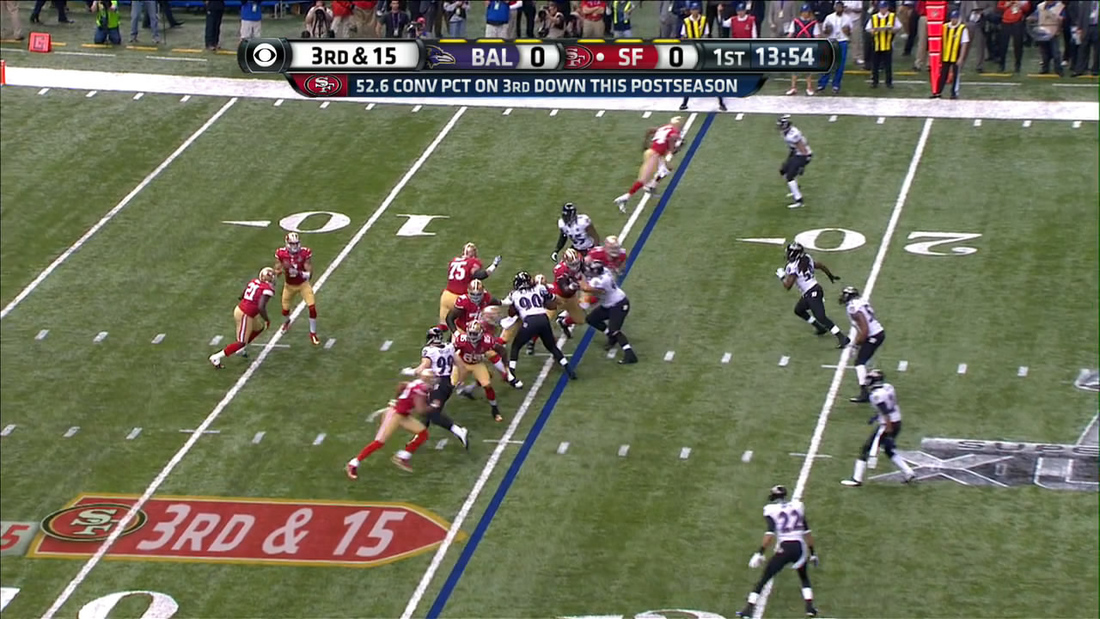

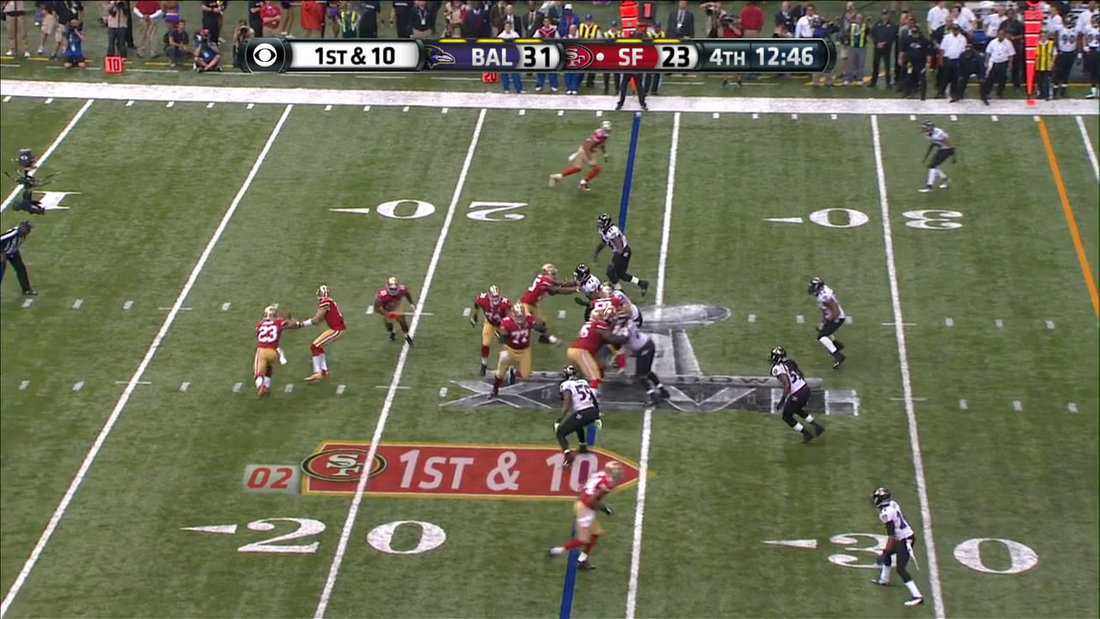

The Ravens bring eight into the box during the Super Bowl.

The Ravens bring eight into the box during the Super Bowl. The Ravens blitz the slot corner (No. 24) and a linebacker to converge at the point of the handoff.

The Ravens blitz the slot corner (No. 24) and a linebacker to converge at the point of the handoff. The Ravens' Paul Kruger (No. 99) attacks the backfield as the "overhang" defender.

The Ravens' Paul Kruger (No. 99) attacks the backfield as the "overhang" defender. The 49ers run a triple option with LaMichael James and Frank Gore in the backfield.

The 49ers run a triple option with LaMichael James and Frank Gore in the backfield.

USA Today Images

USA Today Images

Getty Images

Getty Images

Grant Gelt ("Bertram"), Victor DiMattia ("Timmy Timmons"), Marty York ("Yeah-Yeah"), Chauncey Leopardi ("Squints"), David Mickey Evans (director)

Grant Gelt ("Bertram"), Victor DiMattia ("Timmy Timmons"), Marty York ("Yeah-Yeah"), Chauncey Leopardi ("Squints"), David Mickey Evans (director) DiMattia and York, who played Timmy Timmons and Yeah-Yeah.

DiMattia and York, who played Timmy Timmons and Yeah-Yeah. Tommy Lasorda with Daniel Zacapa.

Tommy Lasorda with Daniel Zacapa. Leopardi, who played Squints.

Leopardi, who played Squints. Evans (director), "Timmy Timmons", "Bertram", "Squints", "Tommy Timmons" (Shane Obedinksi), "Police Chief", Cathleen Summers (producer), "Yeah-Yeah", "The Babe"

Evans (director), "Timmy Timmons", "Bertram", "Squints", "Tommy Timmons" (Shane Obedinksi), "Police Chief", Cathleen Summers (producer), "Yeah-Yeah", "The Babe"

Courtesy University of New Hampshire

Courtesy University of New Hampshire

USA Today Images

USA Today Images